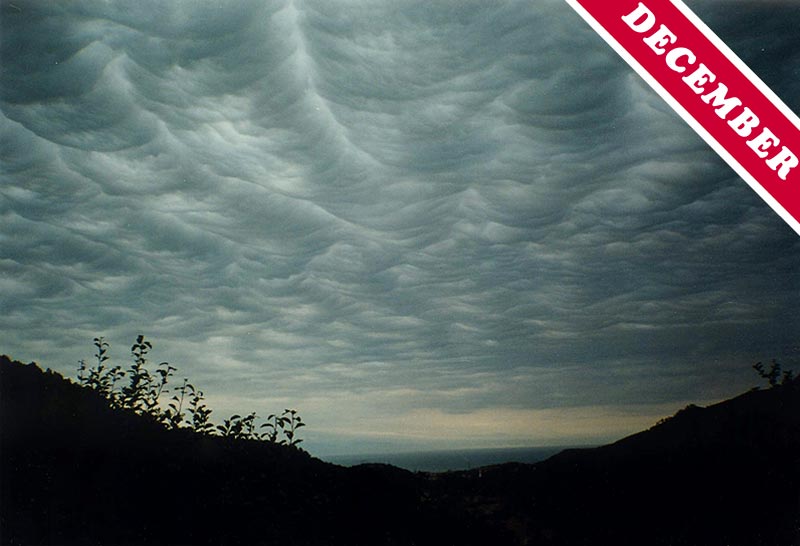

Mamma: the Silly-Season Clouds

Gloriously arresting cloudscapes are, of course, always good news. But when this particularly dramatic formation of mamma clouds* appeared over the UK during August – the holiday season when newsrooms are desperate for something to report – the cloud made the national headlines (The Sun, The Daily Mail, The BBC).

Most meteorology books will tell you that the name of these pendulous cloud features is the Latin for ‘udders’, but few ever agree on what actually makes mamma clouds appear. Why? Because no one really has a clue. ‘Relatively little is known about the formation mechanisms of [mamma],’ stated a 2005 study of them in the Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences (see here). As much as anything, this is because it is very hard to predict when and where they will show up, making it a challenge to be in the right place at the right time to study them.

What we do know is that these pouches can form below of a number of different types of cloud, but the more dramatic examples show up on the underside of the spreading anvil of Cumulonimbus thunder clouds (e.g. see here). Each individual pouch is typically one to three km across and, while they tend to be associated with powerful and dramatic storm clouds, they don’t actually forecast severe weather. This is because mamma generally form at the back, rather than the front, of moving Cumulonimbus clouds. By the time you see them, the storm cloud is already heading off to make news elsewhere.

* Also known as mammatus.

Photographed over St Albans, U.K © Vanessa Sonnabend. See this photo in the Cloud Gallery here.