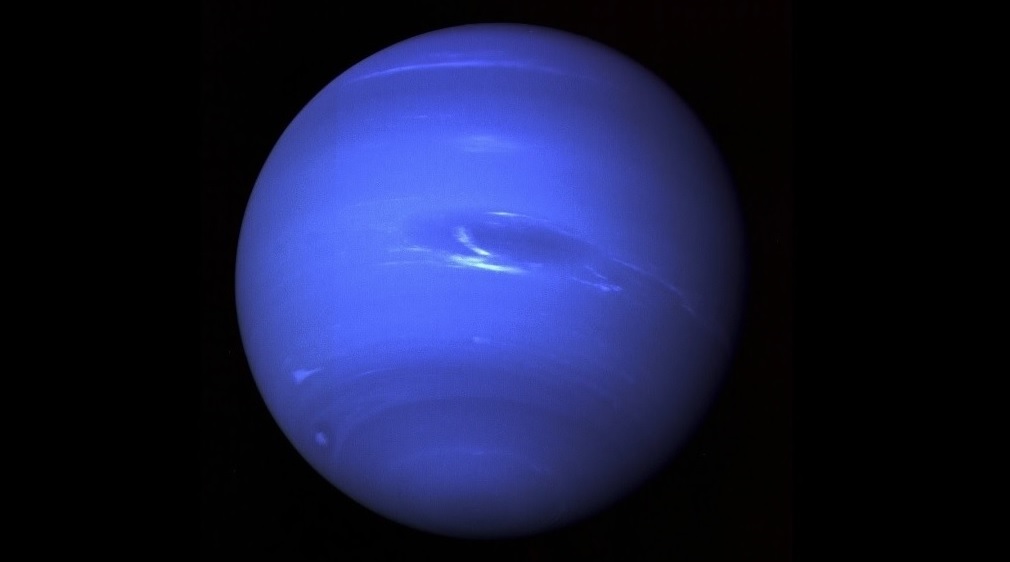

On May 28, 2024, the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) teamed up to launch a 3-year mission called EarthCARE in order to profile Earth’s clouds to see what effect they are having on climate change.

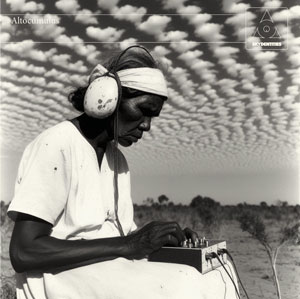

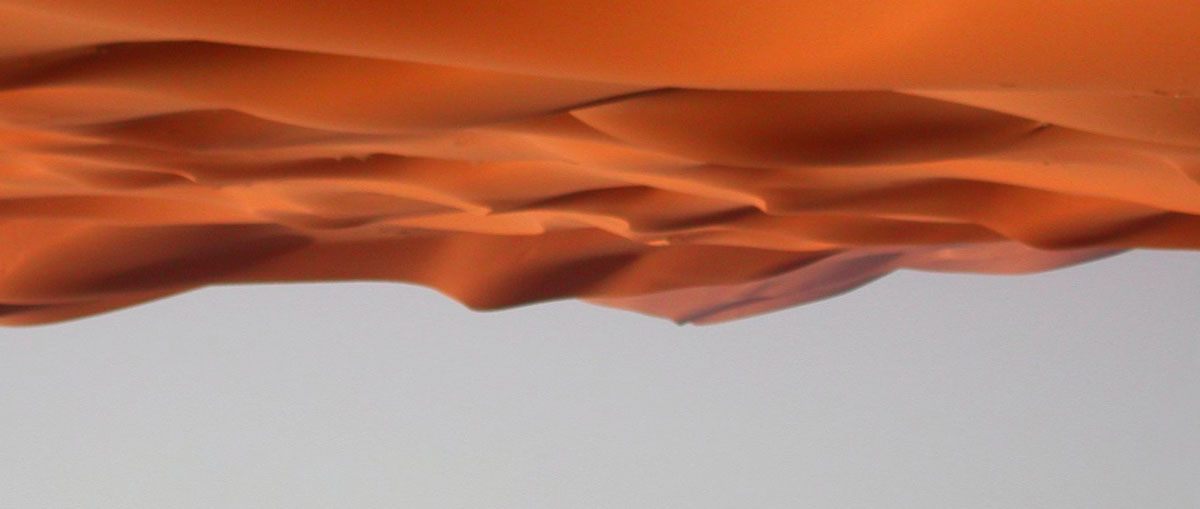

Different cloud formations interact with sunlight in different ways. For example, the low, thick, and puffy Cumulus and Stratocumulus clouds act as giant reflectors, pushing solar radiation back into Space, whereas the high, thin ice-crystal clouds Cirrus and Cirrostratus allow sunlight to easily pass through them but act as giant blankets, trapping in the Earth’s radiation and thus warming surface temperatures. Tiny particles suspended in the atmosphere, known as aerosols, also either reflect or trap solar radiation. It all depends on their composition. Some of the tiny particles are natural, such as desert dust or sea salt, and some unnatural, such as pollution. The aerosols are also crucial in the formation of clouds, for they’re the seeds onto which all cloud droplets and ice crystals form.

But scientists have a long way to go when it comes to understanding the complex interaction between clouds, aerosols, and solar radiation. This is where EarthCARE comes in.

Launched at California’s Vandenberg Space Force Base aboard a Falcon 9 rocket, EarthCARE, an acronym which stands for Earth Cloud Aerosol and Radiation Explorer, is equipped with a variety of instruments able to make 3D profiles of clouds and aerosols in our atmosphere, measuring their compositions and relationships with both reflected solar and emitted thermal radiation, ultimately providing scientists with a better understanding of the role clouds and aerosols play in the global climate.

Along with all this, EarthCARE will be able to provide meteorologists with valuable weather information, such as the speed of precipitation falling from clouds and the intensity of updrafts within Cumulonimbus storm formations – an important indicator of thunderstorm severity.

If you want to find out more about this exciting mission, the website LAist has published a helpful article about it called Unlocking The Clouds and ESA has published an informative short video about it called Unravelling the mysteries of clouds.

Image: ESA