Attached high on the wall of a semi-derelict house at 7 Bruce Grove, Tottenham, London is an English Heritage blue plaque that reads, ‘The Namer of Clouds lived and died here.’ This was the home where Luke Howard spent his last years with his son Robert after his wife, Mariabella, passed away in 1852. Today, almost 160 years after Howard’s death in 1864, his home has been left to crumble by property developers waiting to rebuild it as city apartments. Even if his home can’t be saved, Howard’s legacy lives on in the mind of every child who looks up and learns the names of the clouds. British author Richard Hamblyn, who wrote a brilliant biography of Luke Howard called The Invention of Clouds that was published in 2001, shared a quote from Howard’s grandson Thomas Hodgkin. Contemplating his grandfather’s final years living in this home, Thomas said, ‘I most like to think of him standing on the verandah and watching the dear clouds, the study of which had formed the delight of his life, and which, as I have said before, seemed to be especially beautiful for him.’

Category: Uncategorized

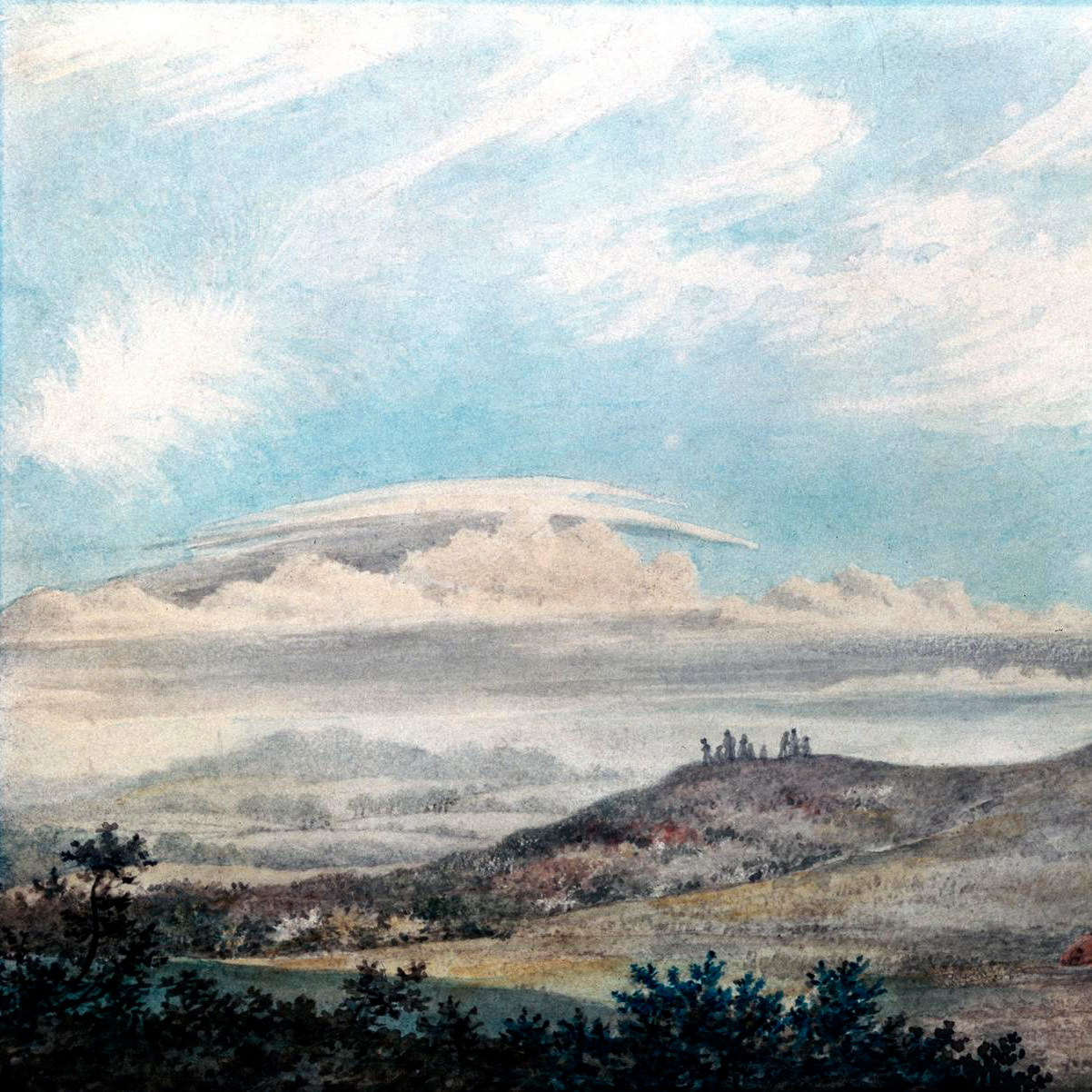

The sky in this watercolour from the first half of the nineteenth century was painted by Luke Howard. He became adept at depicting cloudscapes to use for illustrating his talks and publications about cloud classification. Even though this ‘Godfather of Clouds’ spent much of his time focussed on the inhabitants of the atmosphere, he also cared deeply about those down here on the ground. As a Quaker, Howard was involved in many philanthropic campaigns, including the Society Against Cruelty to Animals, the Society Against Capital Punishment, and the Anti-Slavery Movement. After the 1807 Abolition Act of the British Slave Trade was passed, Howard was one of the founding members of the African Institution, a group which recognised the devastation slavery had caused and worked to remedy it. Luke Howard should be remembered for his rich life of social justice – but not for his artistic skills more broadly. Though his clouds were generally spot-on, Howard was hopeless at painting people and landscapes. He had those added later to his skyscapes by the nineteenth-century landscape artist Edward Kennion.

Detail from a study of clouds by Luke Howard (date uncertain, but before 1849) with the landscape added by Edward Kennion, in the collection of the Science Museum, London.

The World Meteorological Organization – the official keeper of cloud classifications – has rigorously maintained the Latin naming system that Luke Howard first proposed in 1802. But nothing in the world of cloud is ever fixed, and so the system has tended to be revised every few decades, sometimes with new cloud types being added. In 2008, the Cloud Appreciation Society petitioned the WMO to consider adding a new Latin classification for a distinctive cloud spotted by its members around the world. The formation’s chaotic wave-like features resemble a turbulent sea viewed from beneath the surface. In 2006, when Jane Wiggins (Member 15,712) spotted this churning sky over Cedar Rapids, Iowa, US it made the local news. Friends suggested she share her image with the Cloud Appreciation Society, and that’s when we first became aware of this formation. Hers was just one of the hundreds we assembled to support the Society’s proposal. In 2017, the WMO incorporated it as a cloud supplementary feature (a distinctive pattern or form appearing on just a part of one of the main cloud types), giving it the name asperitas, from the Latin for ‘roughness’. Howard’s naming system has evolved incrementally over the centuries as more and more observations of the sky have been shared – enabled most recently by smartphones, the internet, and a growing enthusiasm for citizen science. Today, cloudspotters demonstrate the durability of Luke Howard’s classification system when they learn to identify the common cloud formations and scan the skies for new discoveries.

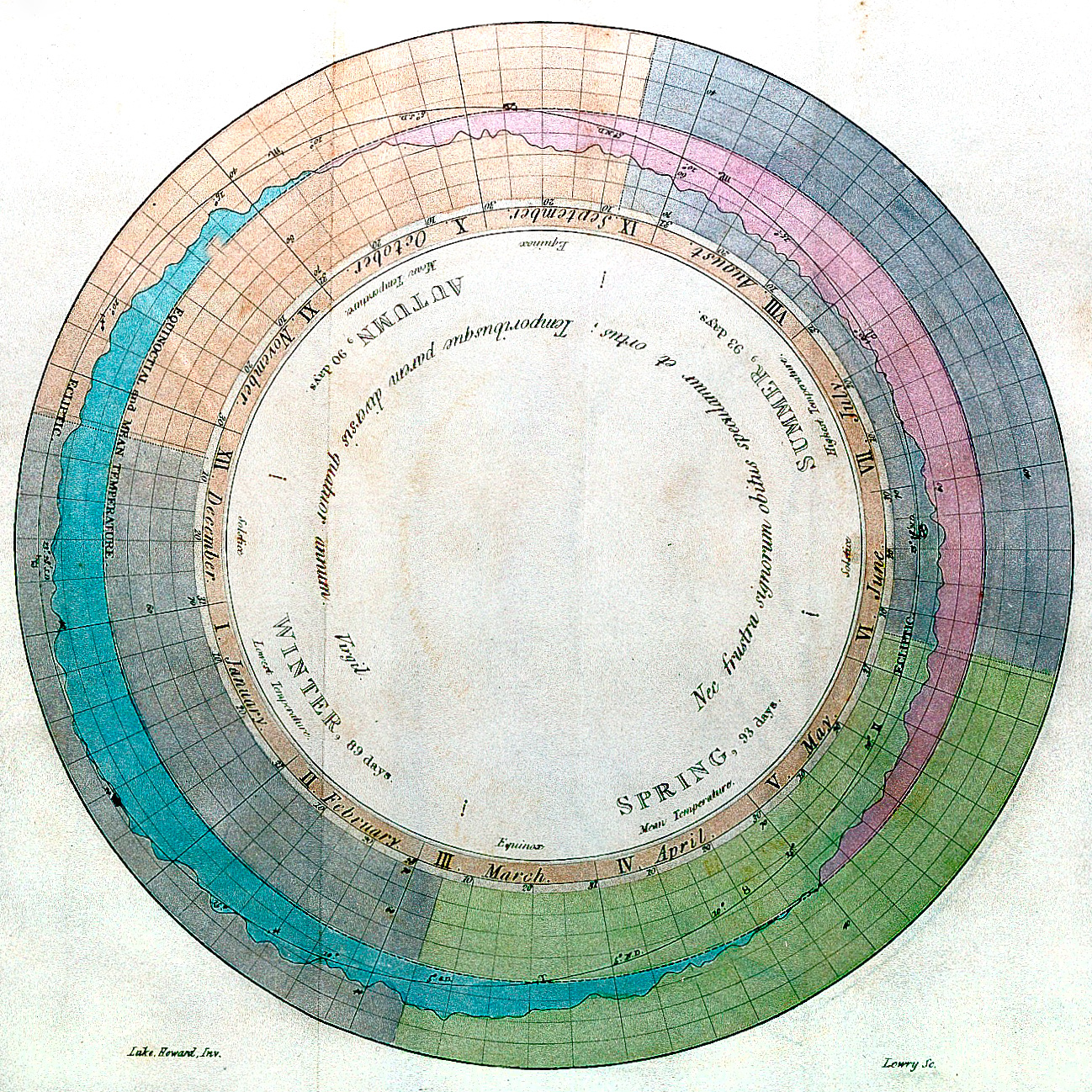

Luke Howard was a tireless and disciplined weather observer who for decades kept daily records of his measurements in and around London. This diagram of the mean temperature throughout the year in the metropolis appeared in the 1833 edition of his book The Climate of London, which was first published in 1818. Through his observations Howard was the first to recognise the effect that urban areas have on local climate. His comparison of temperature records within and outside the capital allowed him to detect, describe, and analyse the phenomenon of ‘urban heat islands’, the fact that average temperatures are higher in cities than in the countryside, many decades before others confirmed it. As he described it, ‘the temperature of the city is not to be considered as that of the climate; it partakes too much of an artificial warmth, induced by its structure, by a crowded population, and the consumption of great quantities of fuel in fires’. He published his book for the enlightenment of his ‘Fellow Citizens’, arguing that science should be studied ‘to bring forth fruits beneficial to his country and to mankind at large’. It is remarkable that Luke Howard, who was subsequently elected a Fellow of the Royal Society, identified virtually all the factors that are today considered responsible for why its warmer in cities than in the country and that he did so in 1820, at the dawn of the scientific study of weather and climate. Encircling his chart of London temperatures is a Latin quotation from the Roman poet Virgil that sums up his dedication to methodical observation: ‘Not in vain do we watch the stars, as they rise and set, and the year, uniform in its four several seasons.’

‘But Howard gives us with his clear mind

The gain of lessons new to all mankind;

That which no hand can reach, no hand can clasp,

He first has gained, first held with mental grasp.

Defin’d the doubtful, fix’d its limit-line,

And named it fitly. – Be the honour thine!

As clouds ascend, are folded, scatter, fall,

Let the world think of thee who taught it all.’

From ‘In Honour of Howard’ (1821), a poem by the German philosopher, natural scientist, and poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, written in admiration of the cloud classification system devised by Luke Howard.

Altocumulus above patches of Altostratus spotted over Goethe’s home town of Weimar in Thüringen, Germany by app user ‘isabel’.

In Luke Howard’s 1802 lecture ‘On the Modifications of Clouds’ he proposed three main cloud families, or ‘simple modifications’ as he called them, which he named Stratus, Cumulus, and Cirrus. These were intended as broad categories of cloud, and Howard summarised each briefly in his lecture. Stratus he defined as ‘a widely extended, continuous, horizontal sheet, increasing from below’, noting also that the lowest of all clouds fall into this group in the form of mist and fog. Cumulus he described as ‘convex or conical heaps, increasing upward from a horizontal base’. Within this family he included fair-weather Cumulus as well as thunder-bearing shower clouds, which we would now refer to as Cumulonimbus. Cirrus he described as ‘parallel, flexuous, or diverging fibres, extensible in any or in all directions’. But Howard’s insight was to conceive of a flexible system that would accommodate the ever-changing mutability of clouds by allowing these broad types to be combined for intermediate forms such as ‘Cirro-stratus’. Howard’s three families are today included as examples of the ten main cloud types – known as the cloud genera, which are defined in terms of their shapes, their altitudes and whether they’re precipitation bearing. Stratus, Cumulus, and Cirrus are therefore now on an equal footing with the likes of Cirrostratus, but Luke Howard’s names and descriptions from over 200 years ago were so well chosen and articulated that they remain essentially unchanged to this day.

Stratus (the low layer) was spotted by ‘Theepot’ over Tineo, Asturias, Spain. Cumulus (the higher individual clumps) was spotted over Dundee, Scotland by Stanley Henderson (Member 26,081). Cirrus (the high streaks) was spotted by Denise Clark Weston over Vancouver, Washington, US.

Rick Shaefer, member 54,615, is an artist who describes himself as “primarily a bread-and-butter Cumulus man. But do spread the tent sometimes”.

Mamma clouds, also known as mammatus, are pouch-like formations named after the Latin for an ‘udder’…

Whispy clouds reflected in a cool sea… another beautiful painting from Lindsay Hopkins Weld.

Lindsay Hopkins Weld lives near the ocean and loves to capture the beauty of nature.

If you are a Cloud Appreciation Society Member and you are have difficulties completing your purchase on the Cloud Shop it is probably because you need to log in. The shop won’t allow two users with the same email address so it won’t let you set up a New Customer account when your email is already on the system as a CAS Member.

Log in as a CAS Member

If you don’t know your username, just use your email address on the login page. If you don’t know your password, click the Lost your Password? link at the bottom of the login page. A new password will be sent to your membership email.

Members login Here Lost your Password?

Still having problems? Email us at membership@cloudappreciationsociety.org

test 2

This video was sent in by Robert Woodward, member number 17865.

‘Test D’ – Cloudscaping from sixdegreesbelowthehorizon on Vimeo.

This video was sent in by Jan van der Zwan, member number 27864

Cloudy Sunrise (HD time lapse) from jan vdz on Vimeo.

This video was sent in by Stephen Ingram

This video was sent in by NicK Palmer, member number 27186.

LookUp from Michal Cipra on Vimeo.

This video was sent in by Tanguy Louvigny, member number 9557.

Hdr skies from Tanguy Louvigny on Vimeo.