The Sky of a Thousand Cloudlets

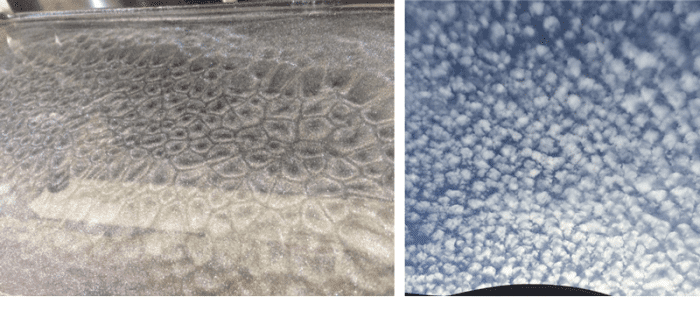

There is something surprising about finding regularity in the natural world – like the uniform hexagon patterns of honeycombs or the intricate fractal swirls found in fern fronds. Another example is the regular arrangement of cloud clumps, known as cloudlets, that make up Altocumulus formations like this one spotted over Huntersville, North Carolina, US by Lauren Antanaitis (Member 25,124). The pattern looks as if some celestial hand has brought order to the usual chaos of the clouds. But this regularity of the sky emerges all by itself. Such patterns are a natural result of the dynamic movement of the gases of air, and they’re something you can reproduce with a demonstration in your own kitchen.

Firstly, here’s what’s happening in the sky when an extended layer of Altocumulus cloudlets (known as Altocumulus stratiformis) appears in a pattern like this. The air up at the cloud level is slightly unstable across a large swathe of the sky due to warmer, less dense air finding itself below distinctly cooler, denser air above. The warmer air starts to float upwards through the cooler. But the whole layer can’t all float up en masse because the cooler air also needs to sink back down to replace it. Currents of air soon arrange themselves into convection cells of rising warm pockets and cooler sinking air in between. Since cloud forms in the pockets of rising air and gaps are left where it’s sinking, the pattern of Altocumulus cloudlets emerges naturally.

You can create the same pattern of convection cells in your kitchen with a panini toaster and some sunflower oil. You’ll also need some mica powder, which is a fine powder used in crafts to add shimmer to paints and is made of crushed mica, a natural stone mineral containing shiny flakes. First, sprinkle some mica powder into a small cup of the sunflower oil. Its sparkle will reveal the oil’s movement. While the sandwich toaster is turned off and still cool, pour onto its plate a shallow layer of the oil mixture about 2mm deep. You’ll need a toaster with a slight lip around the edge of the heating plate so the oil is contained. Now turn the toaster on for just 10 seconds and then off again to warm the oil very gently from below.

The panini toaster doesn’t need to get particularly hot for a pattern to start to appear. After a few seconds, you should see a regular array of circular patches appear in the oil as the mica powder where the oil is rising, with borders where it is sinking. If the pattern of cells doesn’t appear, try another 10-second burst or two to add just a little more warmth. The idea is to heat the oil from below just enough to start it rising. The self-organized rising and sinking currents are known officially as Reyleigh-Bénard convection cells. Whether they’re appearing in swirls of sunflower oil in your kitchen or in swathes of clouds across the vast mid-atmosphere, they are an expression of the beauty of order emerging naturally out of chaos.

Altocumulus stratiformis spotted over Huntersville, North Carolina, US by Lauren Antanaitis (Member 25,124).

Great description and example that paints a picture in my mind I will never forget!

Thanks, Sheryl!